IPA Tutorial: Lesson 1

Just what is the International Phonetic Alphabet (or IPA)? I will use the IPA on this blog and you will hear it used on a number of our accent training resources. You will see it used on countless other linguistics websites as well.If you have no idea what I’m talking about, take a look at this sample:

wʌt ɪz ði aɪ pi eɪ

You may have seen this kind of writing in the pronunciation section

of a dictionary definition. As you can see from the snippet above, the

IPA looks like normal English writing, but with some bizarre letters

thrown in.So what is this weird “alphabet” and why is it so important when studying language?

The International Phonetic Alphabet in a Nutshell

The International Phonetic Alphabet is like any alphabet, except that, where most alphabets form the words of a language, the IPA represents the sounds of a language. Any language, in fact: the IPA can represent nearly any vowel or consonant made by humans.This guide is not designed to explain every nuance of the IPA. Rather, I am going to give you the information you need to start using the IPA. The IPA is like a language: just as you don’t need to memorize every word in the dictionary to use English, you don’t need to know every single symbol in the IPA to starting using it.

But enough introduction. Let’s get started!

How Are Vowels Made?

For the first lesson of our tutorial of the International Phonetic Alphabet, we’re going to take a look at the vowel sounds. Before we look at the vowel symbols of the IPA, it helps to know a bit about how vowels are made.How Humans create Vowel Sounds

Let’s do a little experiment. Make a couple of vowel sounds, like the “ah” in the word “father,” and the “eee” in the word “feet.” Make any combination of vowels. It doesn’t matter what they are.You may notice something when you make these sounds. Your tongue is moving into a lot of different parts of the mouth to create them. That is because vowels are mostly created by the tongue being in a particular position.

For instance, to make the long “eee” sound, I move the tip of my tongue to the topmost, front-most part of my mouth. To make the long “ah” sound I do the opposite: I keep my tongue at the bottom of my mouth.

This is a simple explanation of the process. Most people pronounce vowels using many parts of the vocal apparatus, such as the lips and the jaw. But for the time being, the tongue position is the important thing to understand. If you raise your tongue toward the roof of the mouth, you create one sound; if it’s pushed toward the front of the mouth it creates another sound, etc.

Got it? Okay. Right now you’re probably asking, “weren’t we supposed to learn some crazy alphabet?” Don’t worry. Now we’re getting to the good stuff!

How the IPA Represents Vowels

Okay. We’ve now established that tongue position is important for creating vowel sounds.

So how does the International Phonetic

Alphabet represent this tongue action? To answer this question, let’s

take a look at the standard IPA chart for vowels:

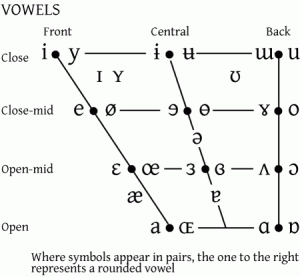

What’s important about this chart is the where each symbol is placed in relation to the other symbols. The rule of thumb for this chart is as follows:

The vowel symbols on the IPA vowel chart are in the position where the tongue is placed when creating a vowel.

Let’s break this down with some examples:

The IPA symbol [i] represents the vowel in American English “feet.” This vowel is pronounced with the tongue high and toward the front. The IPA symbol [ɑ], the vowel in “father,” has the tongue low and to the back. And the IPA symbol [u] (the vowel in American English “goose“) has the tongue high in the mouth and pulled toward the back. Each of these symbols appear on the chart above in about the position that you have to move your tongue to produce them.

But this doesn’t explain all of the symbols in the diagram, does it?

Rounded and Unrounded Vowels in the International Phonetic Alphabet

You will notice that most “positions” in the IPA chart above have two symbols next to each other. The symbol on the left is for an unrounded vowel, meaning that the lips aren’t rounded when you pronounce the sound. The symbol on the right of these positions is the rounded version, meaning the lips are rounded when you pronounce the sound.So, from the IPA chart above, we can deduce the following:

/y/, /u/, /o/ and /ɒ/ are all examples of rounded vowels.

/i/, /ɛ/, /ɑ/, and /a/ are all examples of unrounded vowels.

To clarify, a rounded vowel is a vowel like the “oo” in “room,” while an unrounded vowel might be the “ee” in “fee.” It’s pretty simple principle, really: you will notice that your lips round slightly as you make some vowel sounds, and stay unrounded while making others.

IPA’s “Stand Alone” Vowels

Scroll back up to the IPA chart and take a look at it. I’ll wait down here.You back? Good. You’ll notice on the IPA Chart that there are several vowels that do not appear in pairs. These vowels are: /ʊ/, /ə/, /æ/ and /ɐ/. /ʊ/ is a rounded vowel, while the rest of the “stand alone” vowels are unrounded.

The reason these vowels do not come in pairs is that no languages have been identified which have rounded vowel “phonemes” in these positions. If what I’ve just said completely baffles you, don’t worry. I’ll explain what “phonemes” are in a later lesson. For now, what’s important about these vowels is that they operate in the same way the other symbols do on the IPA chart: they represent where the tongue is place to make them.

The IPA Cheat Sheet

That, more or less, is how the International Phonetic Alphabet creates vowels. Still confused? I’ve created a handy tool so you can “cheat” your way through reading IPA vowels. It’s a list of all the symbols of the IPA, and where they occur in English or other languages.IPA Vowel Symbols

Below is a list of all the vowel symbols of the International Phonetic Alphabet, with an explanation of where you can hear these sounds in different words, dialects and languages.When you first start reading the IPA, I would recommend consulting this chart as much as possible, as well as looking at the standard IPA chart. It won’t take that long for this weird alphabet to be like second nature.

Basic Vowel Symbols

I’ve going break these symbols up into two groups. The first group are “basic” vowel sounds–these are the sounds you most frequently hear in dialects of the English language.The second group of vowels are “other” vowels. You will encounter these somewhat less commonly in English.

| Symbol | English Equivalent |

|---|---|

i |

The “ee” in “Fleece” in most varieties of English. |

ɪ |

The “i” in “Kit” in American & most British dialects |

e |

The “e” in “Bet” in Australian English. Also, the first vowel in the dipthong “face” in American English. |

ɛ |

The “e” in “Dress” in most American and British dialects. |

æ |

The “a” in “Cat” in American English. |

a |

“a” in Scottish English “father” or “a” in Italian and Spanish. The first sound in the American English dipthong “kite” |

ə |

This is the lax, neutral sound in American and British “comma” or “afraid.” It is called the Schwa. |

ɑ |

The “a” in “father” in most American and British accents. The “o” in “not” in American English |

ɒ |

The “o” in “lot” in most British dialects. The “ough” in “thought” in Standard American English |

ɔ |

The “ough” in “Thought” in Standard British and some American accents. |

ʌ |

The “u” in “Strut” in American English. |

o |

The “oa” in “Goat” in many Irish Accents. The “ough” in “thought” in many modern British accents. Also, the first vowel in the dipthong “goat” in American English. |

ʊ |

The vowel in “Foot” or “could” in American English and Standard British English. |

u |

The vowel in “goose” in American English. |

Advanced Vowel Symbols

Then there are the less common, or less commonly-used symbols, which are as follows.| Symbol | English Equivalent |

|---|---|

y |

Like the “ee” in American English “fleece” except with the lips rounded. Can be heard in a few Scottish dialects in the word “goose.” This is also the “u” in French “tu.” |

ʏ |

Like the “i” in American English “kit”, except with the lips rounded. Some London and Scottish accents use this to pronounce “Goose.” |

ø |

Like the “eh” in “bet,” except with the lips rounded. Used in very few English dialects. The “ur” in “nurse” in strong New Zealand accents. |

œ |

Like the “eh” in “bet,” except with the lips rounded (like [2] above, only with the tongue a bit lower). Used in very few English dialects. Possibly the “ur” in “nurse” in very strong Cockney accents. |

ɐ |

The “u” in “Strut” in many modern British dialects. This sound is like /a/ described above, except with the tongue very slightly higher in the mouth. |

ɜ |

A bit like the “ur” in “nurse” in standard british English. The middle of the tongue is placed more or less in the middle of the mouth, and the lips are unrounded. |

ɞ |

Like /ɜ/ above, except the lips are rounded. |

ɘ |

Like /ə/ above, except with the tongue very slightly higher in the mouth. |

ɵ |

Like ɘ above, except with the lips rounded. |

ʉ |

This is a fairly common sound in English, but requires a bit of explanation. This is the “oo” sound in “goose” as it is pronounced in many London dialects, California English and many Scottish dialects. It is like the “oo” in Standard American “goose,” except with the tongue drawn further forward in the mouth. |

ɨ |

Like /ʉ/ above, except the lips are not rounded. |

ɤ |

Like /o/ above except the lips are NOT rounded. Extremely rare in English and most other languages for that matter. A bit like the “u” sound in Japanese. |

ɯ |

Like /u/ above, except the lips are NOT rounded. Like /ɤ/ above, this is very rare in English and other languages. Again, it’s a bit similar to the “u” in Japanese. |

IPA takes a little while to get used to, but once you get it, it’s easy to understand!

All done? Good. Now let’s move on to the consonants, and Lesson Two of our International Phonetic Alphabet tutorial.

IPA Tutorial: Lesson 2

In the previous lesson of our International Phonetic Alphabet Tutorial, we dealt with the symbols used to represent vowel sounds. In this lesson, we will examine consonant symbols.The IPA Consonant Chart

Let’s look at the chart of IPA consonant symbols:

More crazy-looking letters, huh? If you’re overwhelmed, I don’t blame you. As with the vowels, the trick is to learn how this chart works, rather than memorizing every one of these symbols.

Let’s break down the IPA consonant chart so it’s a little more digestible.

Where Consonants Are Produced

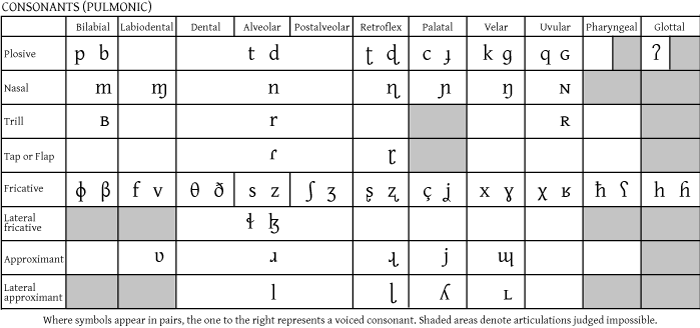

You’ll notice that there is a row of phrases at the top of the chart above with brainy words like “bilabial,” “labiodental,” “dental,” etc. You’ll also notice there is a column on the left side of the chart with additional obscure terminology, such as “plosive,” “nasal,” “trill,” etc. Let’s look at what these words mean.The row of phrases on the top of the chart refers to the part of the vocal apparatus that is used to create the consonant. ( “Vocal apparatus,” by the way, is just another way of saying any part of the body that use to create speech. The vocal apparatus contains your tongue, your throat, your lungs, and many other body parts.)

So this row of fancy phrases on the chart is actually describing something really simple: the part of the body you use to create that sound. “Bilabial,” for example, means you make the sound with your lips.

There’s a simple trick here, which you may have already stumbled upon. On the IPA consonant chart, sounds are written out left to right based on how front or back they are created in the mouth.

So for example, the left-most column of consonants is produced at the very front of the mouth (the lips), whereas the right-most column of consonants is produced at the very back of the throat (the glottis).

With this in mind, you can use the chart above to deduce where in the mouth certain symbols are produced. For example:

/p/, /b/, /m/, /ʙ/, /ɸ/, and /β/ are produced at the front of the mouth (the lips).

/ʔ/, /h/ and /ɦ/ are produced at the very back of the throad (the glottis).

(As usual, don’t worry about what these symbols mean for now.)

But we’ve only talked about the phrases on the top of the consonant chart. What about the words on the left hand side of the chart? What I term the consonants “qualities?” What do I mean by “quality?”

Consonant “Quality”

In reality, what I refer to as “Consonant Qualities” is technically called the manner of articulation. But I think “quality” works as shorthand.To give you an example of what I mean by the “quality” of consonants let’s look at two basic consonants: the “b” in “bed” and the “m” in “man.” Pronounce both of these sounds, one after the other. Go ahead. I’ll wait.

You’ll notice that both of these sound are pronounced with your lips being pressed together. Because of this, they are both grouped together as “bilabial” consonants, which, as I mentioned, is just a fancy word for “sounds that are created with both lips.”

But “m” and “b” are not the same consonant. That’s because they have different “qualities.” The “m” consonant is a “nasal” consonant, meaning it is pronounced while engaging the nasal cavity. The “b” sound, however, is a “plosive.” That means it is pronounced with the lips “popping” or “exploding” with air. (Other plosives include the “t,” “d” and “k” sounds in English. All of these “plosive” sounds involve a part of the mouth being closed shut, then released with a sharp burst of air.)

Scroll back up and take a look at the IPA Consonant Chart. To review, the phrases at the top of the chart are the parts of the vocal apparatus used to make these consonants. The phrases on the left-hand side of the chart are the particular quality (or manner of articulation) of these sounds.

Just get familiar with the terminology. And refer to this cheat sheet if there’s a symbol you don’t understand.

Still confused? Don’t worry. The truth is, consonant sounds in IPA are a bit more intuitive than the vowels. In English, with a few exceptions, the consonants in IPA are fairly similar to the way we write them with the normal alphabet!

There are, however, a few consonant that we use for the English language that a little bizarre. And these are the topic of Lesson Three.

IPA Tutorial: Lesson 3

In the last lesson in our International Alphabet Tutorial, I mentioned that IPA consonant symbols in English are pretty simple. That’s because IPA symbols used to write consonants in most dialects of English are exactly the same as they are in “regular” writing.The following symbols are completely self-explanatory: /p/, /b/, /t/, /d/, /k/, /g/, /m/, /n/, /f/, /v/, /s/, /z/, /h/, /l/. Simple, right?

But there are a few IPA symbols used in English which aren’t quite so cut and dried.

Unusual Consonant Symbols in English

So what are the consonant symbols used in English which are harder to read? They are:/ɹ/ — This represents the standard (American & British) English “r.” You may wonder why the “r” is upside down. That’s because /r/ in IPA represents the “trilled r” you hear in Spanish, Italian and Russian. In most English accents, “r” is pronounced as an “approximant.” That means that the tongue is in about the same position as with the Spanish “r,” but doesn’t actually touch any part of the mouth.

/j/ — in IPA, /j/ represents the “y” in English “yes.” Please note that this symbol in IPA is NOT the “j” in words like “juice” or “just.”

/ʃ/ — this represents the “sh” sound in “shoot.”

/ʒ/ — this is the “voiced” version of /ʃ/. This can be heard in words like “leisure” and “measure.”

/ʧ/ — this is the sound heard in the word “chocolate.” You’ll notice that this is actually a combination of /t/ and /ʃ/.

/ʤ/ — the voiced version of /ʧ/. You can heard this sound in the words “judge” and “Jack.”

/θ/ — this is the sound you hear in the word “thing.”

/ð/ — this is the voiced version of /θ/. You can heard it in the words “this,” “the,” and “mother.”

The other IPA symbols for English are really easy. In fact, if you’re primarily interested in the IPA to learn English dialects, I wouldn’t worry too much about consonants until you have a more advanced understanding of English phonology and phonetics. Consonants vary a lot less in English than many other languages.

By the way, the reason I’m focusing so much on English sounds here is because I think the best way to learn IPA is to start with your own language. Hopefully one day there will be a similar tutorial for Spanish or Czech speakers!

A Quick Review

At this point, it’s okay if you’re not grapsing the difference between a fricative and an approximant. What’s most important is that you understand the following:1.) The IPA is an alphabet used to write out sounds of human language.

2.) The IPA writes out vowels based on where the tongue is positioned making that vowel.

3.) These positions correspond to the position in the IPA vowel chart.

4.) The IPA’s consonants chart is based on the part of the vocal apparatus used to make consonants and the quality of the consonant (manner of articulation).

If you don’t grasp these points, feel free to go back and re-read any of these lessons. I’m sure you’ll get it!

Our next, and final lesson will deal with a few last minor points. On to Lesson Four!

IPA Tutorial: Lesson 4

Thus far in this tutorial, we’ve gone over vowel and consonant symbols in the International Phonetic Alphabet. These are the most important parts of learning the IPA. However, there are a few last details we have to go over.Phonemes and Allophones

I am now going to cover two linguistics terms that are important to fully grasping the IPA.The first term is “phoneme”. A phoneme is a single sound in a language that means something different from another sound. For example, “cat” and “cot” obviously are different words with different meanings. We know this because the “a” and the “o” in these words are different phonemes. We pronounce “a” differently from “o” because we don’t want different words to be confused.

But there is a slight problem here, which can be summed up in one word: “allophones.”Allophones are different ways of pronouncing a single phoneme.

Confused? Let’s look at an example.

Let’s say somebody from London were to pronounce the words “goose” and “pool.” Even though the “oo” sound is one single phoneme, a Londoner would pronounce the two words with different allophones. “Goose” is pronounced by most Londoners with a centralized vowel: in the IPA this would probably be written gʉs. But a Londoner would most likely pronounce “pool” with a back vowel: in IPA this would be written pul. This is due to some phonological processes that I won’t get into here. The point is that even though our Londoner pronounces these two words differently, the “oo” is still the same phoneme.

I’ll give you another example: the word “cut.” Although we think of the “uh” sound in “cut” as a single sound, I’ve probably pronounced this single sound any number of ways: IPA [kʌt], [kɜt], [kət], or [kɐt] depending on how fast I’m speaking, who I’m talking to, and any other number of factors. But although I may technically say this word in a number of different ways, the “uh” sound in “cut” is still the same phoneme. The variations in pronunciation are allophones of this phoneme.

Broad vs. Narrow Transcription

So where does this talk of phonemes and allophones come into play when dealing with the International Phonetic Alphabet?This discussion brings us to an important distinction in the IPA: “broad transcription“vs. “narrow transcription.” Broad transcription is what we do to write the phonemes of a particular person’s dialect. Narrow transcription is what we do to write the exact pronunciation of that dialect or a particular speaker of the dialect.

Let’s look at an example. Suppose I say the sentence “I went to the store and bought a nice bottle of wine.”

If I were to broadly transcribe this sentence in my own dialect (General American), it would read:

/aɪ wɛnt tə ðə stɔɚ ənd bɔt ə naɪs bɑɾɫ əv waɪn/

Never mind if you don’t understand some of the symbols above. The point is that the transcription above is broad transcription

It’s rough estimate of how a General American speaker (like myself)

would say this sentence. Now let’s compare this sentence to a narrow transcription of my pronunciation:

/a:ɪ wɛnt tə ðə stɔɚ ən bɑ?t ə næɪs bɑɾɫ ə wa:ɪn/

There are a lot more quirks and variations in the second transcription. You’ll also notice an interesting marking — [:].

This is an example of “diacritic.” Basically we use little markings

like this if we need to express something in IPA that can’t be described

with the regular notation.In the sentence above, for example, I use [:] after [a] to indicate that that vowel is “long,” or pronounced for a longer duration than we normally would.

There are many many diacritics, which are simply too numerous for me to mention here. I’d recommend that when you see diacritics, you reference this article on Wikipedia — this gives a complete list of IPA diacritics, and you can link to other Wikipedia pages that explain more thoroughly what each diacritic means. (Yes, Cranky McProfessor, I know that Wikipedia is full of garbage. But some of their entries for phonetics and phonology topics aren’t bad starting places).

Anyway, I wouldn’t worry about diacritics too much for now. They aren’t the fundamental building blocks of the IPA. You’ll learn them bit by bit.

Conclusion

We’ve come to the end of our brief IPA tutorial. I want to reiterate that this is a very incomplete description of the IPA. What I’ve attempted to do here is give you the bare minimum information you need to know to understand what is written on this site and other sites that discuss English dialects and languages.Now use it to have a practically perfect performance!

"if you reach for the stars

all you get are the stars

but we've found a whole new spin

if you reach for the heavens

you get the stars thrown in"

-Mary Poppins